Medical records play a crucial role in malpractice cases, as they serve as the primary source of evidence in determining whether or not healthcare providers acted negligently. Thorough and accurate medical records are essential for ensuring that justice is served in these types of claims.

When reviewing medical records in malpractice cases, it is important to pay attention to detail and ensure that all relevant information is documented correctly. Missing or inaccurate information can have serious consequences, potentially leading to incorrect judgments and unfair outcomes for patients who have suffered harm due to medical negligence.

In addition, thorough and accurate medical records provide a clear timeline of events, which can help establish a causal link between a healthcare provider's actions and a patient's injury. This timeline can be instrumental in proving that the standard of care was not met, leading to a successful malpractice claim.

Furthermore, detailed medical records can also help healthcare providers defend themselves against false accusations of malpractice. By documenting all aspects of patient care accurately, providers can demonstrate that they followed proper procedures and acted in the best interest of their patients.

Overall, the importance of thorough and accurate medical records in malpractice cases cannot be overstated. They serve as a critical piece of evidence in determining liability and ensuring that justice is served for patients who have been harmed by medical negligence. Healthcare providers must prioritize maintaining detailed and precise documentation to protect both themselves and their patients.

When it comes to reviewing medical records for malpractice claims, there are several important steps that need to be taken in order to ensure a thorough and accurate evaluation.

The first step is to gather all relevant medical records related to the patient's treatment. This may include hospital records, doctor's notes, test results, and any other documentation that pertains to the care provided. It is important to review these records carefully, paying close attention to details such as dates, times, and specific actions taken by healthcare providers.

Once the records have been collected, the next step is to analyze them in detail. This involves looking for any discrepancies or inconsistencies in the documentation, as well as identifying any potential errors or omissions that may have occurred during the patient's treatment. It is also important to compare the information in the medical records with standard medical guidelines and practices in order to determine whether the care provided was appropriate.

After analyzing the medical records, it is crucial to consult with medical experts who can provide insight into whether malpractice may have occurred. These experts can help identify any deviations from accepted standards of care and offer opinions on whether negligence or wrongdoing took place. Their expertise is invaluable in determining the strength of a malpractice claim.

Finally, once all of these steps have been completed, it is necessary to compile a comprehensive report outlining the findings of the medical record review. This report will serve as a crucial piece of evidence in any malpractice claim and will help support your case if litigation becomes necessary.

In conclusion, reviewing medical records for malpractice claims requires careful attention to detail, thorough analysis, consultation with experts, and meticulous documentation of findings. By following these steps diligently, you can ensure that your evaluation is thorough and accurate, increasing your chances of success in seeking justice for patients who have been harmed by negligent healthcare providers.

Expert witnesses play a crucial role in medical malpractice cases, providing vital information and testimony that can greatly impact the outcome of a case.. These individuals are typically highly qualified professionals who have specialized knowledge and experience in the medical field relevant to the specific case at hand. One of the main functions of expert witnesses in medical malpractice cases is to help educate the judge and jury on complex medical concepts and procedures.

Posted by on 2024-11-14

Medical malpractice law is an ever-evolving field that constantly adapts to new technologies, practices, and challenges in the healthcare industry.. Recent developments in medical malpractice law have brought about significant changes that aim to protect patients' rights and hold healthcare providers accountable for their actions. One of the key recent developments in medical malpractice law is the increased use of telemedicine.

Posted by on 2024-11-14

In the world of medical malpractice claims, one of the most crucial aspects is reviewing the patient's medical records. These records serve as a primary source of information to assess the standard of care provided by healthcare professionals and to determine if any errors or discrepancies exist that may have led to harm or injury.

Unfortunately, common errors and discrepancies are frequently found in medical records, which can significantly impact the outcome of malpractice claims. One prevalent issue is incomplete documentation, where important details about a patient's condition, treatment plan, or follow-up care are missing. This lack of information can make it challenging for legal experts to accurately assess whether proper care was delivered.

Another common error is illegible handwriting, which can lead to misinterpretation or misunderstanding of critical information. Inaccurate or inconsistent charting also poses a significant problem, as conflicting data can create confusion about the timeline of events and the course of treatment.

Moreover, failure to update medical records in a timely manner can result in outdated information being relied upon during legal proceedings. Additionally, incorrect coding or billing practices may misrepresent the services rendered to a patient, leading to potential financial implications for both parties involved.

To mitigate these issues and ensure accurate documentation in medical records, healthcare providers must prioritize thoroughness and clarity in their charting practices. Regular training on proper documentation techniques and standards can help reduce errors and discrepancies that could impact malpractice claims.

In conclusion, understanding and addressing common errors and discrepancies in medical records are essential components of conducting an effective review in malpractice claims. By improving documentation practices and maintaining accurate patient records, healthcare professionals can enhance transparency, accountability, and ultimately provide better quality care to their patients.

Expert witnesses play a crucial role in analyzing medical records for malpractice claims. When it comes to reviewing medical records, these professionals are highly trained and experienced in their field, making them invaluable assets in legal cases involving medical negligence.

Their expertise allows them to decipher complex medical jargon and identify any errors or discrepancies that may have occurred during the course of treatment. By carefully examining each document, expert witnesses can provide insights into whether the standard of care was met or if there was any deviation from accepted medical practices.

Moreover, these experts can offer opinions on causation, helping to establish a link between the alleged malpractice and the harm suffered by the patient. Their testimony carries weight in court due to their credibility and specialized knowledge, which can significantly impact the outcome of a malpractice claim.

In essence, expert witnesses serve as impartial evaluators of medical records, offering an objective analysis that can strengthen a plaintiff's case or provide a defense for healthcare providers. Their role is vital in ensuring that justice is served and that patients receive proper compensation for any harm they have endured due to medical negligence.

When it comes to medical malpractice claims, the review of medical records plays a crucial role in determining the outcome of the case. The legal implications of this process are significant and can greatly impact both patients and healthcare providers.

Medical records are considered legal documents that provide a detailed account of a patient's medical history, treatment, and care received. In malpractice claims, these records are used as evidence to establish whether or not a healthcare provider deviated from the standard of care expected in their field. This information is essential in determining whether negligence or misconduct occurred, leading to harm or injury to the patient.

The review of medical records in malpractice claims must be conducted with great care and attention to detail. Any discrepancies or inconsistencies found in the records could potentially undermine the credibility of either party involved in the case. It is essential for all parties to ensure that the information contained in the records is accurate and complete, as any errors or omissions could have serious legal consequences.

For patients, the review of medical records can be an emotional and stressful process as they relive past experiences and potentially traumatic events. It is important for patients to have access to their medical records and understand their rights when it comes to reviewing and obtaining copies of these documents.

Healthcare providers also have a responsibility to maintain accurate and up-to-date medical records that reflect the care provided to their patients. Failure to do so could result in legal repercussions, including malpractice claims and disciplinary action by licensing boards.

In conclusion, the legal implications of medical records review in malpractice claims are complex and far-reaching. Patients rely on these records as evidence to support their claims, while healthcare providers must ensure that their documentation accurately reflects the care they have provided. It is essential for all parties involved in malpractice claims to approach the review of medical records with diligence and professionalism to ensure fair outcomes for all involved.

Reviewing medical records in malpractice claims can be a complex and challenging process. One of the main challenges is ensuring that all relevant information is accurately documented and interpreted. Medical records are often filled with technical terminology and abbreviations that may not be easily understood by those without a medical background. This can make it difficult for reviewers to fully grasp the details of a case and identify any potential errors or negligence.

Another challenge is the sheer volume of paperwork involved in reviewing medical records. Patients' files can contain years' worth of information, including test results, treatment plans, and progress notes. Reviewers must carefully sift through this mountain of documentation to find pertinent details that support or refute a malpractice claim.

In addition, medical records are often inconsistent or incomplete, which can further complicate the review process. Physicians may fail to document key information such as discussions with patients or decisions made during treatment. This lack of thorough documentation can make it challenging for reviewers to piece together the sequence of events leading up to an alleged malpractice incident.

Furthermore, navigating patient privacy laws and obtaining consent to access medical records adds another layer of complexity to the review process. Reviewers must ensure that they are following all legal guidelines and obtaining proper authorization before accessing sensitive patient information.

Despite these challenges, thorough review of medical records is essential in determining the validity of a malpractice claim. By overcoming these obstacles and conducting a comprehensive analysis of all available evidence, reviewers can help ensure that justice is served in cases involving alleged medical negligence.

Orange County | |

|---|---|

| County of Orange | |

|

Clockwise from top: aerial view of the coast of Newport Beach; Mission San Juan Capistrano; Laguna Beach; Knott’s Berry Farm; and Sleeping Beauty Castle in Disneyland | |

Interactive map of Orange County | |

Location in California | |

| Coordinates: 33°40′N 117°47′W / 33.67°N 117.78°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | California |

| Region | Greater Los Angeles |

| Incorporated | August 1, 1889[1] |

| Named for | The orange, named so the county would sound like a semi-tropical, mediterranean region to people from the east coast[1] |

| County seat | Santa Ana |

| Largest city | Anaheim (population) Irvine (area) |

| Government | |

| • Type | Council–CEO |

| • Body | |

| • Chair | Donald P. Wagner (R) |

| • Vice Chair | Doug Chaffee (D) |

| • County Executive Officer | Frank Kim |

| Area | |

| • Total | 948 sq mi (2,460 km2) |

| • Land | 799 sq mi (2,070 km2) |

| • Water | 157 sq mi (410 km2) |

| Highest elevation | 5,690 ft (1,730 m) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 3,186,989 |

| • Estimate (2023) | 3,186,997 |

| • Density | 3,989/sq mi (1,540/km2) |

| Demonym | Orange Countian |

| GDP | |

| • Total | $314.177 billion (2022) |

| Time zone | UTC−8 (Pacific Time Zone) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−7 (Pacific Daylight Time) |

| Area codes | 562, 657/714, 949 |

| Congressional districts | 38th, 40th, 45th, 46th, 47th, 49th |

| Website | ocgov |

Orange County (officially the County of Orange; often known by its initials O.C.) is a county located in the Los Angeles metropolitan area in Southern California, United States. As of the 2020 census, the population was 3,186,989,[4] making it the third-most-populous county in California, the sixth-most-populous in the United States, and more populous than 19 American states and Washington, D.C.[6] Although largely suburban, it is the second-most-densely-populated county in the state behind San Francisco County.[7] The county's three most-populous cities are Anaheim, Santa Ana, and Irvine, each of which has a population exceeding 300,000.[8] Santa Ana is also the county seat. Six cities in Orange County are on the Pacific coast: Seal Beach, Huntington Beach, Newport Beach, Laguna Beach, Dana Point, and San Clemente.

Orange County is included in the Los Angeles–Long Beach–Anaheim Metropolitan Statistical Area. The county has 34 incorporated cities. Older cities like Tustin, Santa Ana, Anaheim, Orange, and Fullerton have traditional downtowns dating back to the 19th century, while newer commercial development or "edge cities" stretch along the Interstate 5 (Santa Ana) Freeway between Disneyland and Santa Ana and between South Coast Plaza and the Irvine Business Complex, and cluster at Irvine Spectrum. Although single-family homes make up the dominant landscape of most of the county, northern and central Orange County is relatively more urbanized and dense as compared to those areas south of Irvine, which are less dense, though still contiguous and primarily suburban rather than exurban.

The county is a tourist center, with attractions like Disneyland Resort, Knott's Berry Farm, Mission San Juan Capistrano, Huntington Beach Pier, the Richard Nixon Presidential Library and Museum, Modjeska House, Segerstrom Center for the Arts, Yost Theater, Bowers Museum, Balboa Island, Angel Stadium, Downtown Santa Ana, Crystal Cove Historic District, the Honda Center, the Old Orange County Courthouse, the Irvine Ranch Natural Landmarks, and several popular beaches along its more than 40 mi (64 km) of coastline. It is also home to a major research university, the University of California, Irvine (UCI), along with a number of other notable colleges and universities such as Chapman University and Cal State Fullerton.

Archeological evidence shows the area to have been inhabited beginning about 9,500 years ago.[10] At the time of European contact, the northern area of what is now Orange County was primarily inhabited by the Tongva indigenous people, a part of Tovaangar, while the southern area of the county, below Aliso Creek, was primarily inhabited by the Acjachemen.[11][12] Both groups lived in villages throughout the area. Large villages were sometimes multiethnic and multilingual, such as Genga, located in what is now Newport Beach. The village was shared by the Tongva and Acjachemen.[13] The village of Puhú was located in what is now Black Star Canyon and was shared by multiple groups, including the Tongva, Acjachemen, Serrano and Payómkawichum.[14]

The mother village of the Acjachemen was Putiidhem and is now located in San Juan Capistrano underneath Junipero Serra Catholic High School.[15][16] For the Tongva, north Orange County was at the southern extent of their village sites.[17] In coastal villages like Lupukngna, at least 3,000 years old located in what is now Huntington Beach, villagers likely used te'aats or plank boats to navigate the coastline, with fish and shellfish being more central to the diet.[18][19] In inland villages such as Hutuknga, rabbit and mule deer were more central, in addition to acorns from oak trees and seeds from grasses and sage bushes common everywhere.[20]

After the 1769 expedition of Gaspar de Portolà, a Spanish expedition led by Junipero Serra named the area Valle de Santa Ana (Valley of Saint Anne).[22] On November 1, 1776, Mission San Juan Capistrano became the area's first permanent European settlement. Among those who came with Portolá were José Manuel Nieto and José Antonio Yorba. Both these men were given land grants—Rancho Los Nietos and Rancho Santiago de Santa Ana, respectively.[23]

The Nieto heirs were granted land in 1834. The Nieto ranches were known as Rancho Los Alamitos, Rancho Las Bolsas, and Rancho Los Coyotes. Yorba heirs Bernardo Yorba and Teodosio Yorba were also granted Rancho Cañón de Santa Ana (Santa Ana Canyon Ranch) and Rancho Lomas de Santiago, respectively. Other ranchos in Orange County were granted by the Mexican government during the Mexican period in Alta California.[23]

Saint Junípero Serra y Ferrer and the early components of the Portolá Expedition arrived in modern-day San Diego, south of present-day Orange County, in mid-late 1769. During these early Mission years, however, the early immigrants continued to rely on imports of both Mexican-grown and Spanish-grown wines; Serra repeatedly complained of the process of repeated, labored import.[24] The first grape crop production was produced in 1782 at San Juan Capistrano, with vines potentially brought through supply ships in 1778.[24]

Viticulture became an increasingly important crop in Los Angeles and Orange Counties through the subsequent decades. By the 1850s, the regions supported more than 100 vineyards.[25] In 1857, Anaheim was founded by 50 German-Americans (with lineage extending back to Franconia) in search of a suitable grape-growing region.[26] This group purchased a 1,165 acres (4.71 km2) parcel from Juan Pacifico Ontiveros's Rancho San Juan Cajon de Santa Ana for $2 per acre and later formed the Anaheim Vineyard Company.[27][25] With surveyor George Hansen, two of the wine colony's founders, John Frohling and Charles Kohler, planted 400,000 grapevines along the Santa Ana River; by 1875, "there were as many as 50 wineries in Anaheim, and the city's wine production topped 1 million gallons annually."[25] Despite later afflictions of both Phylloxera and Pierce's Disease, wine growing is still practiced.[28]

A severe drought in the 1860s devastated the prevailing industry, cattle ranching, and much land came into the possession of Richard O'Neill Sr.[29] James Irvine and other land barons. In 1887, silver was discovered in the Santa Ana Mountains, attracting settlers via the Santa Fe and Southern Pacific Railroads. High rates of Anglo migration gradually moved Mexicans into colonias, or segregated ethnic enclaves.[30]

After several failed attempts in previous sessions, the California State Legislature passed a bill authorizing the portion of Los Angeles County south of Coyote Creek to hold a referendum on whether to remain part of Los Angeles County or to secede and form a new county to be named "Orange" as directed by the legislature. The referendum required a 2/3 vote for secession to take place, and on June 4, 1889, the vote was 2,509 to 500 in favor of secession. After the referendum, Los Angeles County filed three lawsuits to prevent the secession,[citation needed] but their attempts were futile.[citation needed]

On July 17, 1889, a second referendum was held south of the Coyote Creek to determine if the county seat of the new county would be Anaheim or Santa Ana, along with an election for every county officer. Santa Ana defeated Anaheim in the referendum. With the referendum having passed, the County of Orange was officially incorporated on August 1, 1889.[31] Since the incorporation of the county, the only geographical changes made to the boundary was when the County and Los Angeles County traded some parcels of land around Coyote Creek to conform to city blocks.[when?]

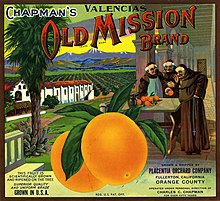

The county is said to have been named for the citrus fruit in an attempt to promote immigration by suggesting a semi-tropical paradise – a place where anything could grow.[32]

In 1919, the California State Legislature redefined the county's boundary with Los Angeles County to no longer follow Coyote Creek but instead along Public Land Survey System township lines instead.[33]

Other citrus crops, avocados, and oil extraction were also important to the early economy. Orange County benefited from the July 4, 1904, completion of the Pacific Electric Railway, a trolley connecting Los Angeles with Santa Ana and Newport Beach. The link made Orange County an accessible weekend retreat for celebrities of early Hollywood. It was deemed so significant that Pacific City changed its name to Huntington Beach in honor of Henry E. Huntington, president of the Pacific Electric and nephew of Collis Huntington. Transportation further improved with the completion of the State Route and U.S. Route 101 (now mostly Interstate 5) in the 1920s.

In the 1910s, agriculture in Orange County was largely centered on grains, hay, and potatoes by small farmers, accounting for 60% of the county's exports. The Segerstroms and Irvines once produced so many lima beans that the county was called "Beanville".[34] By 1920, fruit and nut exports exploded, which led to the increase of industrialized farming and the decline of family farms. For example, by 1917, William Chapman came to own 350,000 acres in northeastern Orange County from the Valencia orange.[35] Around the 1910s and 1920s, most of the barrios of Orange County, such as in Santa Ana, further developed as company towns of Mexican laborers, who worked in the industrial orange groves.[36] Poor working conditions resulted in the Citrus Strike of 1936, in which more than half of the orange industry's workforce, largely Mexican, demanded better working conditions. The strike was heavily repressed, with forced evictions and state-sanctioned violence being used as tactics of suppression.[37] Carey McWilliams referred to the suppression as "the toughest violation of civil rights in the nation."[30]

The Los Angeles flood of 1938 devastated some areas of Orange County, with most of the effects being in Santa Ana and Anaheim, which were flooded with six feet of water. As an eight-foot-high rush of water further spilled out of the Santa Ana Canyon, forty-three people were killed in the predominately Mexican communities of Atwood and La Jolla in Placentia.[38] The devastation from this event, as well as from the 1939 California tropical storm, meant that Orange County was in need of new infrastructure, which was supported by the New Deal. This included the construction of numerous schools, city halls, post offices, parks, libraries, and fire stations, as well as the improvement of road infrastructure throughout Orange County.[39]

School segregation between Mexican and white students in Orange County was widespread in the mid-1940s, with 80% of Mexican students attending 14 segregated schools. These schools taught Mexican children manual education – or gardening, bootmaking, blacksmithing, and carpentry for Mexican boys and sewing and homemaking for girls – while white schools taught academic preparation.[40] The landmark case Mendez vs. Westminster (1947) desegregated Orange County schools, after the Mendez family were denied enrollment into the 17th Street School in Westminster in 1944, despite their cousins with lighter skin being admitted, and were instead told to enroll at the Hoover Elementary School for Mexican children.[41]

In the 1950s, agriculture, such as that involving the boysenberries made famous by Buena Park native Walter Knott, began to decline. However, the county's prosperity soared during this time. The completion of Interstate 5 in 1954 helped make Orange County a bedroom community for many who moved to Southern California to work in aerospace and manufacturing.[42] Orange County received a further economic boost in 1955 with the opening of Disneyland.

In 1969, Yorba Linda-born Orange County native Richard Nixon became the 37th President of the United States. He established a "Western White House" in San Clemente, in South Orange County, known as La Casa Pacifica, and visited throughout his presidency.[43]

In the late 1970s, Vietnamese and Latino immigrants began to populate central Orange County.[44]

In the 1980s, Orange County had become the second most populous county in California as the population topped two million for the first time.

In the 1990s, red foxes became common in Orange County as a non-native mesopredator, with increasing urban development pushing out coyote and mountain lion populations to the county's shrinking natural areas.[45][46]

In 1994, an investment fund meltdown led to the criminal prosecution of treasurer Robert Citron. The county lost at least $1.5 billion through high-risk investments in bonds. The loss was blamed on derivatives by some media reports.[47] On December 6, 1994, the County of Orange declared Chapter 9 bankruptcy,[47] from which it emerged on June 12, 1996.[48] The Orange County bankruptcy was at the time the largest municipal bankruptcy in U.S. history.[47]

Land use conflicts arose between established areas in the north and less developed areas in the south. These conflicts were over issues such as construction of new toll roads and the repurposing of a decommissioned air base. El Toro Marine Corps Air Station was designated by a voter measure in 1994 to be developed into an international airport to complement the existing John Wayne Airport. But subsequent voter initiatives and court actions caused the airport plan to be permanently shelved. It has developed into the Orange County Great Park and housing.[49]

In the 21st century, the social landscape of Orange County has continued to change. The opioid epidemic saw a rise in Orange County, with unintentional overdoses becoming the third highest contributor of deaths by 2014. As in other areas, the deaths disproportionately occurred in the homeless population. However, deaths were widespread among affluent and poorer areas in Orange County, with the highest at-risk group being Caucasian males between the ages of 45–55. A 2018 study found that supply reduction was not sufficient to preventing deaths.[50]

In 2008, a report issued by the Orange County Superior Court found that the county was experiencing a pet "overpopulation problem," with the growing number of pets leading to an increase in euthanasias at the Orange County Animal Shelter to 13,000 for the year alone.[51]

Following the 2016 presidential election, Santa Ana become a sanctuary city for the protection of those immigrants who worked around the legally established process of becoming a legal resident in Orange and other California counties. This created an intense debate in Orange County surrounding politics toward unlawful immigration, with many cities opposing pro-immigration policies.[52]

The COVID-19 pandemic in Orange County disproportionately affected lower income and Latino residents.[53]

Implementation of renewable energy and climate change awareness in Orange County increased, with the city of Irvine pledging to be a zero-carbon economy by 2030 and Buena Park, Huntington Beach, and Fullerton pledging to move to 100% clean energy.[54] Residential solar panel installation has rapidly increased, even among middle-income families, as a result of the state's residential solar program which began in 2006.

In the 2010s, campaigns to conserve remaining natural areas gained awareness.[55][56] By the early 2020s, some success was found, with the conservation of 24 acres in the West Coyote Hills of a total 510 acres and the Genga/Banning Ranch project moving forward, conserving some 385 acres, which was part of the Tongva village area of Genga.[55][56][57] In 2021, the commemorative 1.5 acre Putuidem village opened after years of delays and campaigning by the Acjachemen.[58]

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the county has a total area of 948 sq mi (2,460 km2), of which 791 sq mi (2,050 km2) is land and 157 sq mi (410 km2) (16.6%) is water.[59] It is the smallest county by area in Southern California, being just over 40% the size of the region's next smallest county, Ventura. The average annual temperature is about 68 °F (20 °C).

Orange County is bordered on the southwest by the Pacific Ocean, on the north by Los Angeles County, on the northeast by San Bernardino County, on the east by Riverside County, and on the southeast by San Diego County.

The northwestern part of the county lies on the coastal plain of the Los Angeles Basin, while the southeastern end rises into the foothills of the Santa Ana Mountains. Most of Orange County's population reside in one of two shallow coastal valleys that lie in the basin, the Santa Ana Valley and the Saddleback Valley. The Santa Ana Mountains lie within the eastern boundaries of the county and of the Cleveland National Forest. The high point is Santiago Peak (5,689 ft (1,734 m)[60]), about 20 mi (32 km) east of Santa Ana. Santiago Peak and nearby Modjeska Peak, just 200 ft (60 m) shorter, form a ridge known as Saddleback, visible from almost everywhere in the county. The Peralta Hills extend westward from the Santa Ana Mountains through the communities of Anaheim Hills, Orange, and ending in Olive. The Loma Ridge is another prominent feature, running parallel to the Santa Ana Mountains through the central part of the county, separated from the taller mountains to the east by Santiago Canyon.

The Santa Ana River is the county's principal watercourse, flowing through the middle of the county from northeast to southwest. Its major tributary to the south and east is Santiago Creek. Other watercourses within the county include Aliso Creek, San Juan Creek, and Horsethief Creek. In the North, the San Gabriel River also briefly crosses into Orange County and exits into the Pacific on the Los Angeles-Orange County line between the cities of Long Beach and Seal Beach. Laguna Beach is home to the county's only natural lakes, Laguna Lakes, which are formed by water rising up against an underground fault.

Orange County is sometimes divided into northern and southern regions. There are significant political, demographic, economic and cultural distinctions between North and South Orange County.[61] A popular dividing line between the two regions is the Costa Mesa Freeway.

Northern Orange County, including Anaheim, Fullerton, Garden Grove and Santa Ana, was the first part of the county to be developed and is culturally closer to neighboring Los Angeles County. This region is more Hispanic (mostly Mexican) and Asian (predominantly Vietnamese and Korean),[62] more densely populated (Santa Ana is the one hundredth and one most densely-populated city in the United States with a population of over 300,000), younger, less wealthy and with higher unemployment. It has more renters and fewer homeowners and generally votes Democratic. There are notable exceptions to these general trends, such as strongly Republican Yorba Linda and affluent Anaheim Hills, North Tustin, and Villa Park.[61] Northern Orange County is predominantly flat, giving way to the Santa Ana Mountains in the Northeast.

Southern Orange County is wealthier, more residential, more Republican, predominantly non-Hispanic white, and more recently developed. Irvine, the largest city in the region, is an exception to some of these trends, being not only a major employment center, but also a major tech hub and education center with UCI. Furthermore, the city is an Asian plurality (both South and East Asian), and votes reliably Democratic in recent years. Southern Orange County almost always includes Irvine,[63] Newport Beach, and the cities to their southeast, including Lake Forest, Laguna Niguel, Laguna Beach, Mission Viejo, and San Clemente. Alternatively, Irvine and Newport Beach are sometimes seen as Central Orange County, acting as a transition zone between north and south; when this viewpoint is taken Tustin is also considered to be in Central Orange County. Costa Mesa is sometimes included in South County,[64] although it is located predominantly to the west of the Costa Mesa Freeway and is part of the even street grid network of northern Orange County.[65] Irvine is located in a valley defined by the Santa Ana Mountains and the San Joaquin Hills, while much of Southern Orange County is very hilly.

Another region of Orange County is the Orange Coast, which includes the six cities bordering the Pacific Ocean. These are, from northwest to southeast: Seal Beach, Huntington Beach, Newport Beach, Laguna Beach, Dana Point and San Clemente, although Seal Beach is sometimes viewed as an extension of neighboring Long Beach in Los Angeles County.

Older cities in North Orange County like Santa Ana, Anaheim, Orange and Fullerton have traditional downtowns dating to the late 19th century, with Downtown Santa Ana being the home of the county, state and federal institutions. However, far more commercial activity is concentrated in clusters of newer commercial development located further south in the county's edge cities. The three largest edge cities, from north to south, are:

A contiguous strip of commercial development (an edge city) stretches from Disneyland through to MainPlace Mall along the I-5 Santa Ana Freeway,[66][67][68][69][70] straddling the city limits of Anaheim, Garden Grove, Orange, and Santa Ana, and in fact stretching between the original downtowns of those four cities.

Entertainment and cultural facilities include Disneyland Resort, Angel Stadium, Christ Cathedral (formerly Crystal Cathedral), City National Grove of Anaheim – a live concert venue, Discovery Cube Orange County, the Honda Center – home to the Anaheim Ducks of the NHL (National Hockey League), and the Anaheim Convention Center. Health care facilities include CHOC (Children's Hospital of Orange County), Kaiser Permanente Health Pavilion (Anaheim), St. Joseph Hospital (Orange), and the UCI Medical Center.

Retail complexes include Anaheim GardenWalk, Anaheim Marketplace (claiming to be the largest indoor swap meet in Orange County with more than 200 vendors), MainPlace Mall, Orange Town & Country, and The Outlets at Orange, originally a mall named "The City" which was the centerpiece of a planned, 1970s mixed-use development by the same name. There is commercial strip-style development including big box retailers along West Chapman Avenue in Orange, along Harbor Boulevard in Garden Grove, and around Harbor Boulevard and Chapman Avenue in Anaheim.

Major hotels line Harbor Boulevard from Disneyland south to Garden Grove. The Orange County Transit Authority studied the corridor as the possible route for a streetcar, a proposal that was dropped in 2018 due to opposition from Anaheim and other city governments.[71]

In addition to suburban-style apartment complexes, Anaheim's Platinum Triangle is undergoing transformation from a low-density commercial and industrial zone into a more urban environment with high-density housing, commercial office towers, and retail space. Anaheim envisions it as a "downtown for Orange County".[72] The 820 acres (330 ha) area undergoing this large-scale redevelopment includes the city's two major sports venues, the Honda Center and Angel Stadium of Anaheim.[73]

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1890 | 13,589 | — | |

| 1900 | 19,696 | 44.9% | |

| 1910 | 34,436 | 74.8% | |

| 1920 | 61,375 | 78.2% | |

| 1930 | 118,674 | 93.4% | |

| 1940 | 130,760 | 10.2% | |

| 1950 | 216,224 | 65.4% | |

| 1960 | 703,925 | 225.6% | |

| 1970 | 1,420,386 | 101.8% | |

| 1980 | 1,932,709 | 36.1% | |

| 1990 | 2,410,556 | [75] | 24.7% |

| 2000 | 2,846,289 | [75] | 18.1% |

| 2010 | 3,010,232 | [76] | 5.8% |

| 2020 | 3,186,989 | [77] | 5.9% |

| 2023 (est.) | 3,135,755 | [78] | −1.6% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[79][failed verification] 1790–1960[80] 1900–1990[81] | |||

| Race / Ethnicity (NH = Non-Hispanic) | Pop 1990[82] | Pop 2000[83] | Pop 2010[76] | Pop 2020[77] | % 1990 | % 2000 | % 2010 | % 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White alone (NH) | 1,554,501 | 1,458,978 | 1,328,499 | 1,198,655 | 64.49% | 51.26% | 44.13% | 37.61% |

| Black or African American alone (NH) | 39,159 | 42,639 | 44,000 | 49,304 | 1.62% | 1.50% | 1.46% | 1.55% |

| Native American or Alaska Native alone (NH) | 8,584 | 8,414 | 6,216 | 5,298 | 0.36% | 0.30% | 0.21% | 0.17% |

| Asian alone (NH) | 240,756 | 383,810 | 532,477 | 699,124 | 9.99% | 13.48% | 17.69% | 21.94% |

| Pacific Islander alone (NH) | N/A | 8,086 | 8,357 | 7,714 | N/A | 0.30% | 0.28% | 0.24% |

| Some Other Race alone (NH) | 2,728 | 4,525 | 5,593 | 14,818 | 0.11% | 0.28% | 0.19% | 0.46% |

| Mixed Race or Multi-Racial (NH) | N/A | 64,258 | 72,117 | 125,242 | N/A | 2.26% | 2.40% | 3.93% |

| Hispanic or Latino (any race) | 564,828 | 875,579 | 1,012,973 | 1,086,834 | 23.43% | 30.76% | 33.65% | 34.10% |

| Total | 2,410,556 | 2,846,289 | 3,010,232 | 3,186,989 | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% |

| Population, race, and income | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total population[84] | 2,989,948 | ||||

| White[84] | 1,852,969 | 62.0% | |||

| Black or African American[84] | 49,513 | 1.7% | |||

| American Indian or Alaska Native[84] | 12,548 | 0.4% | |||

| Asian[84] | 532,499 | 17.8% | |||

| Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander[84] | 9,331 | 0.3% | |||

| Hispanic or Latino (of any race)[85] | 994,279 | 33.3% | |||

| Per capita income[86] | $34,416 | ||||

| Median household income[87] | $75,762 | ||||

| Median family income[88] | $85,009 | ||||

| Place | Type[89] | Population[90] | Per capita income[86] | Median household income[citation needed] | Median family income[88] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aliso Viejo | City | 47,037 | $44,646 | $99,095 | $113,183 |

| Anaheim | City | 335,057 | $23,109 | $59,330 | $63,180 |

| Brea | City | 38,837 | $36,195 | $81,278 | $98,159 |

| Buena Park | City | 80,214 | $23,470 | $64,809 | $68,872 |

| Costa Mesa | City | 109,796 | $33,800 | $65,471 | $74,201 |

| Coto de Caza | CDP | 14,974 | $65,625 | $164,385 | $176,686 |

| Cypress | City | 47,610 | $32,815 | $82,954 | $92,276 |

| Dana Point | City | 33,510 | $51,431 | $83,306 | $101,186 |

| Fountain Valley | City | 55,209 | $35,487 | $81,661 | $91,003 |

| Fullerton | City | 134,079 | $30,967 | $69,432 | $78,812 |

| Garden Grove | City | 170,148 | $21,066 | $60,036 | $62,820 |

| Huntington Beach | City | 189,744 | $42,127 | $80,901 | $99,038 |

| Irvine | City | 205,057 | $43,102 | $92,599 | $109,762 |

| Ladera Ranch | CDP | 21,412 | $48,671 | $132,475 | $143,857 |

| Laguna Beach | City | 22,808 | $81,591 | $99,190 | $139,833 |

| Laguna Hills | City | 30,477 | $44,751 | $85,971 | $105,385 |

| Laguna Niguel | City | 62,855 | $51,491 | $100,480 | $119,757 |

| Laguna Woods | City | 16,276 | $36,017 | $35,393 | $50,332 |

| La Habra | City | 60,117 | $24,589 | $63,356 | $69,028 |

| Lake Forest | City | 77,111 | $39,844 | $94,632 | $108,211 |

| La Palma | City | 15,536 | $34,475 | $84,693 | $92,757 |

| Las Flores | CDP | 5,911 | $46,717 | $128,269 | $135,046 |

| Los Alamitos | City | 11,442 | $38,527 | $79,861 | $90,409 |

| Midway City | CDP | 8,052 | $18,610 | $46,714 | $55,168 |

| Mission Viejo | City | 93,076 | $41,436 | $96,420 | $109,693 |

| Newport Beach | City | 84,417 | $80,872 | $108,946 | $151,773 |

| North Tustin | CDP | 24,572 | $55,038 | $109,629 | $119,543 |

| Orange | City | 135,582 | $32,797 | $78,654 | $88,423 |

| Placentia | City | 50,089 | $30,451 | $78,364 | $90,372 |

| Rancho Santa Margarita | City | 47,769 | $41,787 | $104,167 | $116,540 |

| Rossmoor | CDP | 10,099 | $51,210 | $108,427 | $119,727 |

| San Clemente | City | 62,052 | $47,894 | $89,289 | $107,524 |

| San Juan Capistrano | City | 34,455 | $39,097 | $73,806 | $86,744 |

| Santa Ana | City | 325,517 | $16,564 | $54,399 | $53,111 |

| Seal Beach | City | 24,157 | $44,115 | $50,958 | $94,035 |

| Stanton | City | 38,141 | $20,558 | $51,933 | $53,968 |

| Sunset Beach | CDP | 1,486 | $47,415 | $68,036 | $109,125 |

| Tustin | City | 74,625 | $32,854 | $73,231 | $80,963 |

| Villa Park | City | 5,825 | $71,697 | $151,139 | $165,833 |

| Westminster | City | 89,440 | $23,201 | $56,867 | $61,145 |

| Yorba Linda | City | 63,578 | $49,485 | $115,291 | $128,528 |

The 2010 United States Census reported that Orange County had a population of 3,010,232. The racial makeup of Orange County was 1,830,758 (60.8%) White (44.0% non-Hispanic white), 50,744 (1.7%) African American, 18,132 (0.6%) Native American, 537,804 (17.9%) Asian, 9,354 (0.3%) Pacific Islander, 435,641 (14.5%) from other races, and 127,799 (4.2%) from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 1,012,973 persons (33.7%).[91]

The Hispanic and Latino population is predominantly of Mexican origin; this group accounts for 28.5% of the county's population, followed by Salvadorans (0.8%), Guatemalans (0.5%), Puerto Ricans (0.4%), Cubans (0.3%), Colombians (0.3%), and Peruvians (0.3%).[92] Santa Ana with its population reportedly 75 percent Hispanic/Latino, is among the most Hispanic/Latino percentage cities in both California and the U.S., esp. of Mexican-American descent.[93]

Among the Asian population, 6.1% are Vietnamese, followed by Koreans (2.9%), Chinese (2.7%), Filipinos (2.4%), Indians (1.4%), Japanese (1.1%), Cambodians (0.2%), Pakistanis (0.2%), Thais (0.1%), Indonesians (0.1%), and Laotians (0.1%).[92] According to KPCC in 2014, Orange County has the largest proportion of Asian Americans in Southern California, where one in five residents are Asian American.[94] There is also a significant Muslim population in the county.[95]

| Population reported at 2010 United States Census | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

The County |

Total Population |

two or more races |

|||||||

| Orange County | 3,010,232 | 1,830,758 | 67,708 | 18,132 | 537,804 | 9,354 | 435,641 | 127,799 | 1,012,973 |

Total Population |

two or more races |

||||||||

| Aliso Viejo | 47,823 | 34,437 | 967 | 151 | 6,996 | 89 | 2,446 | 2,737 | 8,164 |

| Anaheim | 336,265 | 177,237 | 9,347 | 2,648 | 49,857 | 1,607 | 80,705 | 14,864 | 177,467 |

| Brea | 39,282 | 26,363 | 1,549 | 190 | 7,144 | 69 | 3,236 | 1,731 | 9,817 |

| Buena Park | 80,530 | 36,454 | 3,073 | 862 | 21,488 | 455 | 14,066 | 4,132 | 31,638 |

| Costa Mesa | 109,960 | 75,335 | 1,640 | 686 | 8,654 | 527 | 17,992 | 5,126 | 39,403 |

| Cypress | 47,802 | 26,000 | 1,444 | 289 | 14,978 | 234 | 2,497 | 2,360 | 8,779 |

| Dana Point | 33,351 | 28,701 | 294 | 229 | 1,064 | 37 | 1,952 | 1,074 | 5,662 |

| Fountain Valley | 55,313 | 31,225 | 1,510 | 229 | 18,418 | 171 | 2,445 | 2,315 | 7,250 |

| Fullerton | 135,161 | 72,845 | 4,138 | 842 | 30,788 | 321 | 21,439 | 5,788 | 46,501 |

| Garden Grove | 170,883 | 68,149 | 3,155 | 983 | 63,451 | 1,110 | 28,916 | 6,119 | 63,079 |

| Huntington Beach | 189,992 | 145,661 | 1,813 | 992 | 21,070 | 635 | 11,193 | 8,628 | 32,411 |

| Irvine | 212,375 | 107,215 | 3,868 | 355 | 83,176 | 334 | 5,867 | 11,710 | 19,621 |

| La Habra | 60,239 | 35,147 | 1,025 | 531 | 5,653 | 103 | 15,224 | 2,556 | 34,449 |

| La Palma | 15,568 | 5,762 | 802 | 56 | 7,483 | 41 | 760 | 664 | 2,487 |

| Laguna Beach | 22,723 | 20,645 | 278 | 61 | 811 | 15 | 350 | 663 | 1,650 |

| Laguna Hills | 30,344 | 22,045 | 520 | 101 | 3,829 | 58 | 2,470 | 1,421 | 6,242 |

| Laguna Niguel | 62,979 | 50,625 | 877 | 219 | 5,459 | 87 | 3,019 | 2,793 | 8,761 |

| Laguna Woods | 16,192 | 14,133 | 110 | 24 | 1,624 | 10 | 90 | 201 | 650 |

| Lake Forest | 77,264 | 54,341 | 1,695 | 384 | 10,115 | 191 | 7,267 | 3,671 | 19,024 |

| Los Alamitos | 11,449 | 8,131 | 324 | 51 | 1,471 | 50 | 726 | 696 | 2,418 |

| Mission Viejo | 93,305 | 74,493 | 1,710 | 379 | 8,462 | 153 | 4,332 | 4,276 | 15,877 |

| Newport Beach | 85,186 | 74,357 | 616 | 223 | 5,982 | 114 | 1,401 | 2,493 | 6,174 |

| Orange | 136,416 | 91,522 | 3,627 | 993 | 15,350 | 352 | 20,567 | 5,405 | 52,014 |

| Placentia | 50,533 | 31,373 | 914 | 386 | 7,531 | 74 | 8,247 | 2,008 | 18,416 |

| Rancho Santa Margarita | 47,853 | 37,421 | 887 | 182 | 4,350 | 102 | 2,674 | 2,237 | 8,902 |

| San Clemente | 63,522 | 54,605 | 511 | 363 | 2,333 | 90 | 3,433 | 2,287 | 10,702 |

| San Juan Capistrano | 34,593 | 26,664 | 293 | 286 | 975 | 33 | 5,234 | 1,208 | 13,388 |

| Santa Ana | 324,528 | 148,838 | 6,356 | 3,260 | 34,138 | 976 | 120,789 | 11,671 | 253,928 |

| Seal Beach | 24,168 | 20,154 | 279 | 65 | 2,309 | 58 | 453 | 850 | 2,331 |

| Stanton | 38,186 | 16,991 | 3,358 | 405 | 8,831 | 217 | 9,274 | 1,610 | 19,417 |

| Tustin | 75,540 | 39,729 | 2,722 | 442 | 15,299 | 268 | 14,499 | 3,581 | 30,024 |

| Villa Park | 5,812 | 4,550 | 92 | 34 | 854 | 1 | 162 | 169 | 598 |

| Westminster | 89,701 | 32,037 | 2,849 | 397 | 42,597 | 361 | 10,229 | 3,231 | 21,176 |

| Yorba Linda | 64,234 | 48,246 | 835 | 230 | 10,030 | 85 | 2,256 | 2,552 | 9,220 |

Total Population |

two or more races |

||||||||

| Coto de Caza | 14,866 | 13,094 | 132 | 26 | 878 | 20 | 174 | 542 | 1,170 |

| Ladera Ranch | 22,980 | 17,899 | 335 | 54 | 2,774 | 27 | 624 | 1,267 | 2,952 |

| Las Flores | 5,971 | 4,488 | 91 | 23 | 780 | 12 | 261 | 316 | 984 |

| Midway City | 8,485 | 2,884 | 71 | 65 | 3,994 | 40 | 1,165 | 266 | 2,467 |

| North Tustin | 24,917 | 20,836 | 148 | 104 | 1,994 | 52 | 908 | 875 | 3,260 |

| Rossmoor | 10,244 | 8,691 | 84 | 36 | 838 | 29 | 168 | 398 | 1,174 |

Other unincorporated areas |

Total Population |

two or more races |

|||||||

| All others not CDPs (combined) | 32,726 | 20,572 | 4,365 | 290 | 3,934 | 144 | 6,113 | 1,272 | 13,247 |

As of the census[96] of 2000, there were 2,846,289 people, 935,287 households, and 667,794 families living in the county, making Orange County the second most populous county in California. The population density was 1,392/km2 (3,606/sq mi). There were 969,484 housing units at an average density of 474/km2 (1,228/sq mi). The racial makeup of the county was 64.8% White, 13.6% Asian, 1.7% African American, 0.7% Native American, 0.3% Pacific Islander, 14.8% from other races, and 4.1% from two or more races. 30.8% were Hispanic or Latino of any race. 8.9% were of German, 6.9% English and 6.0% Irish ancestry according to Census 2000. 58.6% spoke only English at home; 25.3% spoke Spanish, 4.7% Vietnamese, 1.9% Korean, 1.5% Chinese (Cantonese or Mandarin) and 1.2% Tagalog.

In 1990, still according to the census[97] there were 2,410,556 people living in the county. The racial makeup of the county was 78.6% White, 10.3% Asian or Pacific Islander, 1.8% African American, 0.5% Native American, and 8.8% from other races. 23.4% were Hispanic or Latino of any race.

Out of 935,287 households, 37.0% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 55.9% married couples were living together, 10.7% had a female householder with no husband present, and 28.6% were non-families. 21.1% of all households were made up of individuals, and 7.2% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 3.00 and the average family size was 3.48.

Ethnic change has been transforming the population. By 2009, nearly 45 percent of the residents spoke a language other than English at home. Whites now comprise only 45 percent of the population, while the numbers of Hispanics grow steadily, along with Vietnamese, Korean and Chinese families. The percentage of foreign-born residents jumped to 30 percent in 2008 from 6 percent in 1970. The mayor of Irvine, Sukhee Kang, was born in Korea, making him the first Korean-American to run a major American city. “We have 35 languages spoken in our city,” Kang observed.[98] The population is diverse age-wise, with 27.0% under the age of 18, 9.4% from 18 to 24, 33.2% from 25 to 44, 20.6% from 45 to 64, and 9.9% 65 years of age or older. The median age is 33 years. For every 100 females, there were 99.0 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 96.7 males.

The median income for a household in the county was $61,899, and the median income for a family was $75,700 (these figures had risen to $71,601 and $81,260 respectively as of a 2007 estimate[99]). Males had a median income of $45,059 versus $34,026 for females. The per capita income for the county was $25,826. About 7.0% of families and 10.3% of the population were below the poverty line, including 13.2% of those under age 18 and 6.2% of those age 65 or over.

Residents of Orange County are known as "Orange Countians".[100]

Orange County is the headquarters of many Fortune 500 companies including Ingram Micro (#62[101]) and First American Corporation (#476[102]) in Santa Ana, Broadcom (#150) in Irvine, Western Digital (#198[103]) in Lake Forest, and Pacific Life (#269[104]) in Newport Beach. Irvine is the home of numerous start-up companies and also is the home of Fortune 1000 headquarters for Allergan, Edwards Lifesciences, Epicor, and Sun Healthcare Group. Other Fortune 1000 companies in Orange County include Beckman Coulter in Brea, Quiksilver in Huntington Beach and Apria Healthcare Group in Lake Forest. Irvine is also the home of notable technology companies like TV and sound bar company VIZIO, router manufacturer Linksys, video/computer game creator Blizzard Entertainment, and in-flight product manufacturer Panasonic Avionics Corporation. Also, the prestigious Mercedes-Benz Classic Center USA is located in the City of Irvine. Many regional headquarters for international businesses reside in Orange County like Mazda, Toshiba, Toyota, Samsung, Kia, in the City of Irvine, Mitsubishi in the City of Cypress, Kawasaki Motors in Foothill Ranch, and Hyundai in the City of Fountain Valley. Fashion is another important industry to Orange County. Oakley, Inc. is headquartered in Lake Forest. Hurley International is headquartered in Costa Mesa. The network cyber security firm Milton Security Group is located in Brea.[105][106][107][108][109] The shoe company Pleaser USA, Inc. is located in Fullerton. St. John is headquartered in Irvine. Tustin, is home to Ricoh Electronics, New American Funding, and Safmarine. Wet Seal is headquartered in Lake Forest. PacSun is headquartered in Anaheim.[110] Restaurants such as Taco Bell, El Pollo Loco, In-N-Out Burger, Claim Jumper, Marie Callender's, Wienerschnitzel, have headquarters in the city of Irvine as well. Del Taco is headquartered in Lake Forest. Gaikai also has its headquarters in Orange County.

Shopping in Orange County is centered around regional shopping malls, big box power centers and smaller strip malls. South Coast Plaza in Costa Mesa is the largest mall in California, the third largest in the United States, and 31st largest in the world. Other regional shopping malls include (from north to south): Brea Mall, The Village at Orange, The Outlets at Orange, MainPlace Santa Ana, Westminster Mall, Bella Terra in Huntington Beach, The Market Place straddling Tustin and Irvine, Irvine Spectrum Center, Fashion Island in Newport Beach, Five Lagunas and The Shops at Mission Viejo. Downtown Disney and Anaheim GardenWalk are specialized shopping and entertainment centers aimed at visitors. Power centers include La Habra Marketplace, Anaheim Plaza, and Anaheim Town Square. There is one major outlet mall, The Outlets at San Clemente.[111]

Tourism remains a vital aspect of Orange County's economy. Anaheim is the main tourist hub, with the Disneyland Resort's Disneyland being the second most visited theme park in the world. Also, Knott's Berry Farm gets about 7 million visitors annually and is located in the city of Buena Park. The Anaheim Convention Center holds many major conventions throughout the year. Resorts within the Beach Cities receive visitors throughout the year due to their close proximity to the beach, biking paths, mountain hiking trails, golf courses, shopping and dining.

As recently as the 1990s, award-winning restaurants in Orange County consisted mostly of national chain restaurants with traditional American or Tex-Mex comfort food.[citation needed] The Orange County Register states that the "tipping point" came in 2007 when Marneaus founded Marché Moderne (since moved to Crystal Cove), and Top Chef chef Amar Santana opened a branch of Charlie Palmer (closed 2015),[112] both at South Coast Plaza. Santana followed opening restaurants Broadway in Laguna Beach and Vaca in Costa Mesa. Other Top Chef chefs followed with their own restaurants including Brian Huskey (Tackle Box), Shirley Chung (Twenty Eight), Jamie Gwen of Cutthroat Kitchen, and from The Great Food Truck Race, Jason Quinn (Playground), who also opened three stands at the 4th Street Market[113] food hall in Downtown Santa Ana in 2016.[114]

Food halls with gourmet vendors include the 42,000 sq ft (3,900 m2) Anaheim Packing District, the 4th Street Market in Downtown Santa Ana, Lot 579 in Huntington Beach, Trade Food Hall in Irvine,[115] OC Mix in Costa Mesa, and The Source OC in Buena Park.[116]

In 2019, the Michelin Guide awarded stars for the first time to Orange County restaurants, awarding Hana Re and Taco Maria one star each.[117] In 2021, Knife Pleat in Costa Mesa was awarded one Michelin star as well.[118]

The area's warm Mediterranean climate and 42 mi (68 km) of year-round beaches attract millions of tourists annually. Huntington Beach is a hot spot for sunbathing and surfing; nicknamed "Surf City, U.S.A.", it is home to many surfing competitions. "The Wedge", at the tip of The Balboa Peninsula in Newport Beach, is one of the most famous body surfing spots in the world. Southern California surf culture is prominent in Orange County's beach cities. Another one of these beach cities being Laguna Beach, just south of Newport Beach. A few popular beaches include A Thousand Steps on 9th Street, Main Street Beach, and The Montage.

Other tourist destinations include the theme parks Disneyland Park and Disney California Adventure Park in Anaheim and Knott's Berry Farm in Buena Park. Due to the 2022 reopening of Wild Rivers in Irvine, the county is home to three water parks along with Soak City in Buena Park and Great Wolf Lodge in Anaheim.[119] The Anaheim Convention Center is the largest such facility on the West Coast. The Old Towne, Orange Historic District in the City of Orange (the traffic circle at the middle of Chapman Avenue at Glassell Street) still maintains its 1950s image, and appeared in the movie That Thing You Do!.

Little Saigon is another tourist destination, home to the largest concentration of Vietnamese people outside Vietnam. There are also sizable Taiwanese, Filipino, Chinese, and Korean communities, particularly in western Orange County. This is evident in several Asian-influenced shopping centers in Asian American hubs like Irvine. Popular food festival 626 Night Market has a location at OC Fair & Event Center in Costa Mesa and is a popular attraction for Asian and fusion food, as well as an Art Walk and live entertainment.[120]

Historical points of interest include Mission San Juan Capistrano, the renowned destination of migrating swallows. The Richard Nixon Presidential Library and Museum is in Yorba Linda and the Richard Nixon Birthplace, on the grounds of the Library, is a National Historic Landmark. John Wayne's yacht, the Wild Goose or USS YMS-328, is in Newport Beach. Other notable structures include the home of Madame Helena Modjeska, in Modjeska Canyon on Santiago Creek; Ronald Reagan Federal Building and Courthouse in Santa Ana, the largest building in the county; the historic Balboa Pavilion[121] in Newport Beach; and the Huntington Beach Pier. The county has nationally known centers of worship, such as Crystal Cathedral in Garden Grove, the largest house of worship in California; Saddleback Church in Lake Forest, one of the largest churches in the United States; and the Calvary Chapel.

In 2014, the county had 1,075 religious organizations, the sixth-highest total among all US counties (matching its status as the sixth-most-populous county in the US).[122]

Orange County is the base for several religious organizations:

Huntington Beach annually plays host to the U.S. Open of Surfing, AVP Pro Beach Volleyball and Vans World Championship of Skateboarding.[133] It was also the shooting location for Pro Beach Hockey.[134] USA Water Polo, Inc. has moved its headquarters to Irvine, California.[135] Orange County's active outdoor culture is home to many surfers, skateboarders, mountain bikers, cyclists, climbers, hikers, kayaking, sailing and sand volleyball.

The Major League Baseball team in Orange County is the Los Angeles Angels. The team won the World Series under manager Mike Scioscia in 2002. In 2005, new owner Arte Moreno wanted to change the name to "Los Angeles Angels" in order to better tap into the Los Angeles media market, the second largest in the country. However, the standing agreement with the city of Anaheim demanded that they have "Anaheim" in the name, so they became the Los Angeles Angels of Anaheim. This name change was hotly disputed by the city of Anaheim, but the change stood, which prompted a lawsuit by the city of Anaheim against Arte Moreno, won by the latter. Prior to the 2016 season Moreno and the club officially dropped the Anaheim moniker now simply going by the Los Angeles Angels.

The county's National Hockey League team, the Anaheim Ducks, won the 2007 Stanley Cup beating the Ottawa Senators. They also came close to winning the 2003 Stanley Cup finals after losing in Game 7 against the New Jersey Devils.

The Toshiba Classic, the only PGA Champions Tour event in the area, is held each March at The Newport Beach Country Club. Past champions include Fred Couples (2010), Hale Irwin (1998 and 2002), Nick Price (2011), Bernhard Langer (2008) and Jay Haas (2007). The tournament benefits the Hoag Hospital Foundation and has raised over $16 million in its first 16 years.

Orange County SC is a United Soccer League team and are the only professional soccer club in Orange County. The team's first season was in 2011 and it was successful as Charlie Naimo's team made it to the quarter-finals of the playoffs. With home games played at Championship Soccer Stadium in Orange County Great Park the team looks to grow in the Orange County community and reach continued success. Former and current Orange County SC players include Richard Chaplow, Bright Dike, Maykel Galindo, Carlos Borja, and goalkeeper Amir Abedzadeh.

The National Football League left the county when the Los Angeles Rams relocated to St. Louis in 1995.

The National Basketball Association's Los Angeles Clippers played some home games at The Arrowhead Pond, now known as the Honda Center, from 1994 to 1999, before moving to Staples Center (now Crypto.com Arena), which they share with the Los Angeles Lakers.

Orange County is a charter county of California; its seat is Santa Ana.

The elected offices of the county government consist of the five-member board of supervisors, assessor, auditor-controller, clerk-recorder, district attorney-public administrator, sheriff-coroner, and treasurer-tax collector. Except for the board of supervisors, each of these elected officers are elected by the voters of the entire county and oversee their own county departments.[136]

As of January 2023[update], the six countywide elected officers are:[136][137]

A seventh countywide elected officer, the County Superintendent of Schools (jointly with an independently elected County Board of Education) oversees the independent Orange County Department of Education.[138]

Each of the five members of the board of supervisors is elected from a regional district, and together, the board oversees the activities of the county's agencies and departments and sets policy on development, public improvements, and county services. At the beginning of each calendar year, the Supervisors select a chair and Vice Chair amongst themselves. The chair presides over board meetings, and the Vice Chair presides when the chair is not present. The Board appoints the Clerk of the Board of Supervisors, the County Counsel, the Performance Audit Director, and the Director of the Office of Independent Review. The Board also appoints the County Executive Officer to act as the chief administrative officer of the county and the manager of all agencies and departments not under the sole jurisdiction of an elected county official nor the sole jurisdiction of one of the four aforementioned officers appointed by the Board.[139]

As of October 2024[update], the members of the Orange County Board of Supervisors are:[136][137][139]

The County Department of Education is wholly separate from the County government and is jointly overseen by the elected County Superintendent of Schools and the five-member Orange County Board of Education, whose trustees are popularly elected from five separate trustee areas.[138]

As of January 2023[update], the six elected officials overseeing the Orange County Department of Education are:[137][140][141]

On July 12, 2010, it was revealed that former Sheriff Mike Carona received over $215,000 in pension checks in 2009, despite his felony conviction.[142] A 2005 state law denied a public pension to public officials convicted of wrongdoing in office, however, that law only applied to benefits accrued after December 2005. Carona became eligible for his pension at age 50, and is also entitled, by law, to medical and dental benefits.[143][144] It was noted that the county's retirement system faces a massive shortfall totaling $3.7 billion unfunded liabilities, and Carona was one of approximately 400 retired Orange County public servants who received more than $100,000 in benefits in 2009.[145] Also on the list of those receiving extra-large pension checks is former treasurer-tax collector Robert Citron, whose investments, which were made while consulting psychics and astrologers, led Orange County into bankruptcy in 1994.[146]

Citron, a Democrat, funneled billions of public dollars into questionable investments, and at first the returns were high and cities, schools and special districts borrowed millions to join in the investments. But the strategy backfired, and Citron's investment pool lost $1.64 billion. Nearly $200 million had to be slashed from the county budget and more than 1,000 jobs were cut. The county was forced to borrow $1 billion.[147]

The California Foundation for Fiscal Responsibility filed a lawsuit against the pension system to get the list. The agency had claimed that pensioner privacy would be compromised by the release. A judge approved the release and the documents were released late June 2010. The release of the documents has reopened debate on the pension plan for retired public safety workers approved in 2001 when Carona was sheriff.[148]

Called "3 percent at 50," it lets deputies retire at age 50 with 3 percent of their highest year's pay for every year of service. Before it was approved and applied retroactively, employees received 2 percent.[149] "It was right after Sept. 11," said Orange County Supervisor John Moorlach. "All of a sudden, public safety people became elevated to god status. The Board of Supervisors were tripping over themselves to make the motion." He called it "one of the biggest shifts of money from the private sector to the public sector." Moorlach, who was not on the board when the plan was approved, led the fight to repeal the benefit. A lawsuit, which said the benefit should go before voters, was rejected in Los Angeles County Superior Court in 2009 and is now under appeal.[148] Carona opposed the lawsuit when it was filed, likening its filing to a "nuclear bomb" for deputies.[citation needed]

Voter registration as of July 19, 2022[150]

During most of the 20th century and up until 2016, Orange County was known for its political conservatism and for being a bastion for the Republican Party, with a 2005 academic study listing three Orange County cities as among America's 25 most conservative.[151] However, the county's changing demographics have coincided with a shift in political alignments, making it far more competitive in recent years. In 2016, Hillary Clinton became the first Democrat since 1936 to carry Orange County in a presidential election and in the 2018 midterm elections the Democratic Party gained control of every Congressional seat in the county.[152][153][154][155] Although Democrats controlled all congressional districts in Orange County at the time, Republicans maintained a lead in voter registration numbers (although it shrunk to less than a percentage point as of February 10, 2019,[156] as compared with over 10% on February 10, 2013).[157] The number of registered Democrats surpassed the number of registered Republicans in the county in August 2019. As the number of Democrats increased, the number of voters not aligned with a political party increased to comprise 27.4% of the county's voters in 2019.[158] Republicans held a majority on the county Board of Supervisors until 2022, when Democrats established a 3–2 control of the body. Seven out of the 12 state legislators from Orange County are also Republicans.

From the mid-20th century until the 2010s, Orange County was known as a Republican stronghold and consistently sent Republican representatives to the state and federal legislatures—so strongly so, that Ronald Reagan described it as the place that "all the good Republicans go to die."[152] Republican majorities in Orange County helped deliver California's electoral votes to Republican nominees Richard Nixon in 1960, 1968, and 1972; Gerald Ford in 1976; Reagan in 1980 and 1984; and George H. W. Bush in 1988. It was one of five counties in the state that voted for Barry Goldwater in 1964.

In 1936, Orange County gave Franklin D. Roosevelt a majority of its presidential vote. The Republican nominee won Orange County by double digits in the next seventeen presidential elections. Orange County's Republican registration reached its apex in 1991, 55.6% of registered voters.[159] But with the 2008 election it began trending Democratic until Hillary Clinton won the county with an eight-point majority in 2016.[160][161] In 2020, Joe Biden further improved slightly on Clinton's 2016 margin of victory.[162][163] In 2023, the Republican party's registration was 33%, while the Democratic party's registration was 37.5%.[159]

| Year | Republican | Democratic | Third party(ies) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |

| 2020 | 676,498 | 44.44% | 814,009 | 53.48% | 31,606 | 2.08% |

| 2016 | 507,148 | 42.35% | 609,961 | 50.94% | 80,412 | 6.71% |

| 2012 | 582,332 | 51.87% | 512,440 | 45.65% | 27,892 | 2.48% |

| 2008 | 579,064 | 50.19% | 549,558 | 47.63% | 25,065 | 2.17% |

| 2004 | 641,832 | 59.68% | 419,239 | 38.98% | 14,328 | 1.33% |

| 2000 | 541,299 | 55.75% | 391,819 | 40.36% | 37,787 | 3.89% |

| 1996 | 446,717 | 51.67% | 327,485 | 37.88% | 90,374 | 10.45% |

| 1992 | 426,613 | 43.87% | 306,930 | 31.56% | 239,006 | 24.58% |

| 1988 | 586,230 | 67.75% | 269,013 | 31.09% | 10,064 | 1.16% |

| 1984 | 635,013 | 74.70% | 206,272 | 24.27% | 8,792 | 1.03% |

| 1980 | 529,797 | 67.90% | 176,704 | 22.65% | 73,711 | 9.45% |

| 1976 | 408,632 | 62.16% | 232,246 | 35.33% | 16,555 | 2.52% |

| 1972 | 448,291 | 68.27% | 176,847 | 26.93% | 31,515 | 4.80% |

| 1968 | 314,905 | 63.14% | 148,869 | 29.85% | 34,933 | 7.00% |

| 1964 | 224,196 | 55.89% | 176,539 | 44.01% | 430 | 0.11% |

| 1960 | 174,891 | 60.81% | 112,007 | 38.95% | 701 | 0.24% |

| 1956 | 113,510 | 66.82% | 54,895 | 32.31% | 1,474 | 0.87% |

| 1952 | 80,994 | 70.29% | 33,397 | 28.98% | 844 | 0.73% |

| 1948 | 48,587 | 60.88% | 29,018 | 36.36% | 2,209 | 2.77% |

| 1944 | 38,394 | 56.92% | 28,649 | 42.47% | 407 | 0.60% |

| 1940 | 36,070 | 55.49% | 28,236 | 43.44% | 691 | 1.06% |

| 1936 | 23,494 | 43.31% | 29,836 | 55.00% | 921 | 1.70% |

| 1932 | 22,623 | 45.91% | 23,835 | 48.37% | 2,818 | 5.72% |

| 1928 | 30,572 | 79.35% | 7,611 | 19.75% | 344 | 0.89% |

| 1924 | 19,913 | 67.35% | 2,565 | 8.68% | 7,088 | 23.97% |

| 1920 | 12,797 | 71.52% | 3,502 | 19.57% | 1,594 | 8.91% |

| 1916 | 10,609 | 56.59% | 6,474 | 34.54% | 1,663 | 8.87% |

| 1912 | 123 | 1.08% | 4,406 | 38.58% | 6,892 | 60.34% |

| 1908 | 3,244 | 53.74% | 1,911 | 31.65% | 882 | 14.61% |

| 1904 | 2,665 | 59.54% | 1,034 | 23.10% | 777 | 17.36% |

| 1900 | 2,155 | 51.24% | 1,777 | 42.25% | 274 | 6.51% |

| 1896 | 1,932 | 51.06% | 1,712 | 45.24% | 140 | 3.70% |

| 1892 | 1,152 | 39.74% | 1,000 | 34.49% | 747 | 25.77% |

| Year | GOP | DEM |

|---|---|---|

| 2022 | 51.5% 492,734 | 48.5% 464,206 |

| 2021† | 48.3% 547,685 | 51.7% 586,457 |

| 2018 | 49.9% 539,951 | 50.1% 543,047 |

| 2014 | 55.6% 344,817 | 44.4% 275,707 |

| 2010 | 56.8% 499,878 | 37.4% 328,663 |

| 2006 | 69.7% 507,413 | 25.5% 185,388 |

| 2003† | 63.5% 493,850 | 16.8% 130,808 |

| 2002 | 57.5% 368,152 | 34.7% 222,149 |

| 1998 | 52.1% 370,736 | 44.7% 318,198 |

| 1994 | 67.7% 516,811 | 27.7% 211,132 |

| 1990 | 63.7% 425,025 | 31.3% 208,886 |

| 1986 | 71.9% 468,092 | 26.5% 172,782 |

| 1982 | 61.4% 422,878 | 36.7% 252,572 |

| 1978 | 44.2% 272,076 | 48.7% 299,577 |

| 1974 | 56.9% 297,870 | 40.6% 212,638 |

| 1970 | 66.9% 308,982 | 31.5% 145,420 |

| 1966 | 72.2% 293,413 | 27.9% 113,275 |

| 1962 | 59.4% 169,962 | 39.2% 112,152 |

| 1958 | 53.6% 98,729 | 46.3% 85,364 |

| 1954 | 69.7% 63,148 | 30.3% 27,511 |

| 1950 | 75.4% 57,348 | 24.6% 18,711 |

The Republican margin began to narrow in the 1990s and 2000s as the state trended Democratic until the mid- to late-2010s when it voted for the Democratic Party in 2016 and in 2018, when the Democratic party won every United States House District anchored in the county, including four that had previously been held by Republicans.[166] This prompted media outlets to declare Orange County's Republican leanings "dead", with the Los Angeles Times running an op-ed titled, "An obituary to old Orange County, dead at age 129."[152][153][154][155][167] While Republicans were able to recapture two of the seven U.S. House seats in Orange County in 2020, Democrats continued to hold the other five, Biden won the county by a slightly greater margin than Clinton had, and Democrats received a majority of the votes in each of the seven congressional districts.[163] Republicans still carry more weight at the local level, and in 2020 for the State Assembly elections, they won 50.2% of the vote and four out of seven seats of the county.[168] In the 2022 midterm elections, no congressional districts flipped, though Republicans performed strongly in Orange County, with every statewide GOP candidate carrying it.

For the 118th United States Congress in the United States House of Representatives, Orange County is split between six congressional districts:[169]

The 40th, 45th, 46th, and 47th districts are all centered in Orange County. The 38th has its population center in Los Angeles County, while the 49th is primarily San Diego County-based. 132, 154, 188 In the California State Senate, Orange County is split into 7 districts:[169]

In the California State Assembly, Orange County is split into 9 districts:[169]

According to the California Secretary of State, as of February 10, 2019, Orange County has 1,591,543 registered voters. Of these, 34% (541,711) are registered Republicans, and 33.3% (529,651) are registered Democrats. An additional 28.5% (453,343) declined to state a political party.[156]

Orange County has produced notable Republicans, such as President Richard Nixon (born in Yorba Linda and lived in Fullerton and San Clemente), U.S. Senator John F. Seymour (previously mayor of Anaheim), and U.S. Senator Thomas Kuchel (of Anaheim). Former Congressman Christopher Cox (of Newport Beach), a White House counsel for President Reagan, is also a former chairman of the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. Orange County was also home to former Republican Congressman John G. Schmitz, a presidential candidate in 1972 from the ultra-conservative American Independent Party, John Birch Society member, and the father of Mary Kay Letourneau. In 1996, Curt Pringle (later mayor of Anaheim) became the first Republican Speaker of the California State Assembly in decades.

While the growth of the county's Hispanic and Asian populations in recent decades has significantly influenced Orange County's culture, its conservative reputation has remained largely intact. Partisan voter registration patterns of Hispanics, Asians and other ethnic minorities in the county have tended to reflect the surrounding demographics, with resultant Republican majorities in all but the central portion of the county. When Loretta Sanchez, a Blue Dog Democrat, defeated veteran Republican Bob Dornan in 1996, she was continuing a trend of Democratic representation of that district that had been interrupted by Dornan's 1984 upset of former Congressman Jerry Patterson. Until 1992, Sanchez herself was a moderate Republican, and she is viewed as somewhat more moderate than other Democrats from Southern California.

In 2004, George W. Bush captured 60% of the county's vote, up from 56% in 2000 despite a higher Democratic popular vote statewide. Although Barbara Boxer won statewide in the simultaneously held senate election and fared better in Orange County than she did in 1998, Republican Bill Jones defeated her in the county, 51% to 43%. While the 39% that John Kerry received is higher than the percentage Bill Clinton won in 1992 or 1996, the percentage of the vote George W. Bush received in 2004 is the highest any presidential candidate has received since 1988, showing a still-dominant GOP presence in the county. In 2006, Senator Dianne Feinstein won 45% of the vote in the county, the best showing of a Democrat in a Senate race in over four decades, but Orange was nevertheless the only Coastal California county to vote for her Republican opponent, Dick Mountjoy.

The county is featured prominently in Lisa McGirr's book Suburban Warriors: The Origins of the New American Right. She argues that its conservative political orientation in the 20th century owed much to its settlement by farmers from the Great Plains, who reacted strongly to communist sympathies, the civil rights movement, and the turmoil of the 1960s in nearby Los Angeles — across the "Orange Curtain".

In the 1970s and 1980s, Orange County was one of California's leading Republican voting blocs and a subculture of residents with "Middle American" values that emphasized capitalist religious morality[clarification needed] in contrast to West coast liberalism.

Orange County has many Republican voters from culturally conservative Asian-American, Middle Eastern and Latino immigrant groups. The large Vietnamese-American communities in Garden Grove and Westminster are predominantly Republican; Vietnamese Americans registered Republicans outnumber those registered as Democrats, 55% to 22% as of 2007, while as of 2017 that figure is 42% to 36%. Republican Assemblyman Van Tran was the first Vietnamese-American elected to a state legislature and joined with Texan Hubert Vo as the highest-ranking elected Vietnamese-American in the United States until the 2008 election of Joseph Cao in Louisiana's 2nd congressional district. In the 2007 special election for the vacant county supervisor seat following Democrat Lou Correa's election to the state senate, two Vietnamese-American Republican candidates topped the list of 10 candidates, separated from each other by only seven votes, making the Orange County Board of Supervisors entirely Republican; Correa is first of only two Democrats to have served on the Board since 1987 and only the fifth since 1963.

Even with the Democratic sweep of Orange County's congressional seats in 2018, as well as a steady trend of Democratic gains in voter registration, the county remains very Republican downballot. Generally, larger cities–those with a population over 100,000, such as Anaheim, Santa Ana, and Irvine – feature a registration advantage for Democrats, while the other municipalities still have a Republican voter registration advantage. This is especially true in Newport Beach, Yorba Linda, and Villa Park, the three cities where the Republican advantage is largest. As of February 10, 2019, the only exceptions to the former are Huntington Beach and Orange, while exceptions to the latter include Buena Park, Laguna Beach and Stanton.[156]